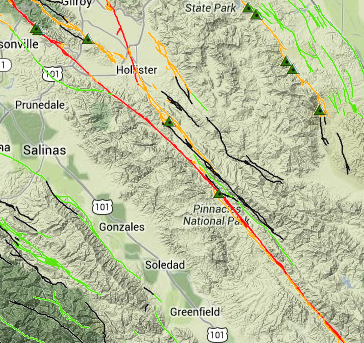

The Monterey Shale runs through some major fault lines, and that’s raised concerns in earthquake-prone California. Could high-pressure pumping under the earth to free the shale’s valuable oil deposits — known as hydraulic fracturing — trigger the next Big One?

It’s a question that seismologists get frequently as the debate heats up over fracking and other methods of extreme energy extraction. It turns out that the seismic danger is not so much linked to fracking itself, but more likely the method of disposing of the wastewater generated from the process.

As seismologist Peggy Hellweg of UC Berkeley’s seismology laboratory explains, the giant thumper trucks that create seismic waves during oil exploration create “a temporary nuisance factor” but the dangers are “relatively small.” The next step when oil is discovered — fracking — involves pumping a mixture of water, sand and chemicals at high pressure deep in the earth until the oil-bearing rocks break up and release tiny tremors.

“But they are very small and way too tiny for anyone to feel,” Hellweg said.

The tremors can register up to a Magnitude 3 earthquake, which are nearly imperceptible, and a far cry from the Magnitude 7 Loma Prieta earthquake, which rocked Northern California in 1989.

“I’m not expecting the Big One to be triggered by this kind of thing,” Hellweg said.

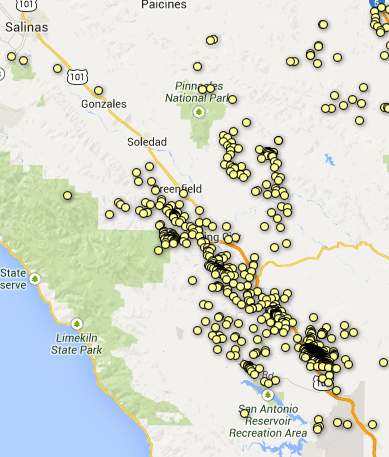

Instead, the underground injection of wastewater from fracking could, in fact, trigger earthquakes at the level of Magnitude 3 to 5, which would be noticeable to most people and could cause damage to poorly constructed buildings. Central California is littered with old injection wells that could become disposal sites for the toxic chemical byproducts of oil extraction.

Oil wells currently located in the upper Monterey Shale. They include exploratory wells and possible sites for injection wells. Source: California Department of Conservation.

As Hellweg explains, even if you use clean water to frack, the “produced water” that comes back out of the well is contaminated with the added chemicals and sometimes extremely low but measurable concentrations of radioactive elements.

“It’s horrible stuff so you can’t just let it roll down the nearest stream. You have to handle it as a hazardous waste,” Hellweg said.

It’s possible to clean this “produced water,” but it’s also expensive, so many operators dispose of it in wastewater injection wells, which are known in the industry as Class II wells that are often nearby.

“Easier than cleaning it up is to pump it down some hole you don’t need any more, and that’s injection” she explains.

Hellweg notes that although there are about 140,000 injection wells in the U.S., “very few” are associated with these larger earthquakes.

“But there are plots that show, the more strongly you inject, the more likely there are to be earthquakes.”

Bill Ellsworth of the US Geological Services (USGS) Earthquake Science Center in Menlo Park agrees quakes could be related to wastewater injection. A 5.6-magnitude quake in Oklahoma in November 2011 is the biggest suspect to date, though geologists disagree whether that was a natural event or the result of fracking-wastewater injections. Ellsworth says better reporting about disposal operations at injection wells is important, and California’s especially robust seismic monitoring systems might help too.

“It would improve our understanding of why only a few injection wells are seismic problem-children,” he said.

Ruining the water supply

Earthquakes are not the only danger created by fracking wastewater. Another pressing concern is underground contamination of water supplies. There’s nothing more sacred in California than water.

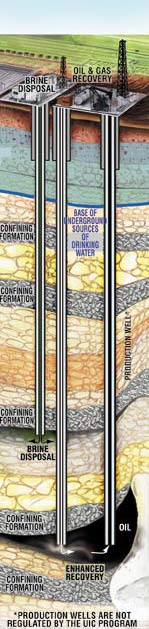

Class II wells, whereby toxic byproducts of oil extraction are pumped underground. Photo: U.S. EPA.

Michael Kiparsky, a researcher at UC Berkeley’s law school, co-authored a report in April 2013 about the the long term risks that fracking presents to the state’s water supply, particularly where developers drill through aquifers en route to the oil reserves below.

“When a hole is drilled, it creates a conduit through which oil, gas, and fracking fluids could move upwards,” Kiparsky says. “If there was a casing failure, that movement into the bottom of the aquifer could happen within hours or days, but wouldn’t necessarily be expressed at the surface, or be visible, for decades or centuries.”

Californians could be living with the effects of fracking long after the boom times end. In his report to UC Berkeley on fracking, Kiparsky warns of the risks of irreversible contamination of surface and groundwater near wells, unless the method is carefully monitored and controlled.

He recommends water quality monitoring, and public disclosure of the chemical contents of fracking fluids, as well as reporting of the location of all injection well sites.

Fracking isn’t the only “well stimulation” method being used to extract oil. Other methods include “steam jobs” and “acid jobs,” or acidization.

- Steam jobs involve injecting steam into shallow wells to raise the temperature of the oil underground, thereby thinning the oil and making it easier to pump.

- In acidization, the chemical action of the acid, often hydrochloric or a mix of hydrochloric and hydrofluoric acids, is used to dissolve minerals in the formation.

Much like fracking, news that acid and steam jobs are taking place in California without regulation, has raised environmental eyebrows and spurred legislators into taking additional action. As State Sen. Fran Pavley noted in August, “Reports indicate that large-scale acid treatments to modify the geologic formation itself may be used, far beyond the traditional periodic acid washing of the wellbore to remove scale.”

Preview to our next and final installment: Sacramento takes on fracking debate

Over the past year, there was a flurry of legislation to further study or tighten the leash on fracking, but most of those efforts failed. Now, State Sen. Fran Pavley has managed to pass SB4, which would regulate all forms of “well stimulation,” including fracking, acid and steam jobs.

Read our first story in Bay Nature’s fracking series: In condor country comes a California oil boom.

Read our second story in the series: Above the Monterey Shale, farmers worry fracking will destroy the land.

Read our third story in the series: Fracking the land of the kit fox, and it’s fellow desert natives.

Read our fourth story in the series: How the Monterey Shale came to be

Sarah Phelan is a contributor to Bay Nature and is leading our coverage on Extreme Energy in the Monterey Shale.