For more information see Adverse Effects, Index Page, Older

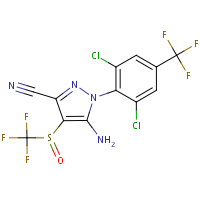

Abstracts, EU 2013 Review.Molecular structure of Fipronil

The organisation representing the UK’s veterinary pharmaceutical sector says “it has not been demonstrated” flea products cause the imidacloprid and fipronil contamination reported in English rivers.

In a comprehensive statement released following the paper by Perkins et al (VT50.48), NOAH accepted both pesticides were present in English rivers between 2016 and 2018, but said neither the source – and whether they were environmentally damaging at the measured levels – “is anything other than conjecture”.

The body pointed out fipronil was not banned for use in farming until September 2017, while use of imidacloprid was only banned at the end of 2018. Both are authorised for other uses – for instance, as biocides – and the latter is used in greenhouses.

Modelling

It said another paper, by Anthe et al in Environmental Sciences Europe, modelled imidacloprid in sewage treatment plant discharges and found pet ectoparasiticides made only a small contribution to the levels found in rivers.

VMD-funded research by vet and University of Sussex PhD student Rosie Perkins, professor of biology Dave Goulson, vet Martin Whitehead and Wayne Civil of the Environment Agency was published in Science of the Total Environment, and widely reported by national media.

Fipronil or its metabolites was found in 98% of samples, and neonicotinoid imidacloprid in 66%. Dr Perkins described the results as “extremely concerning”.

In a statement, released to Vet Times, NOAH said environmental risk assessments were carried out on all authorised veterinary products, with each one assessed by the VMD and regulatory authorities for their benefits versus risks.

Other factors

The statement said: “The consequences of failing to prevent certain parasites can have a high cost not only to pets and their welfare, but also to pet owners due to the distress caused, with possible consequences for the human-animal bond. A failure to prevent disease can also have a negative impact on human health.

“As with all veterinary medicines, prescribers and users of these products should use them responsibly, and advice and warnings on labels and leaflets should be followed. Advice around disposal of products and advice relating to bathing of dogs, or allowing them access to waterways after treatment, should be noted and followed closely.”

“The paper by Perkins et al that was the subject of media coverage in November 2020 raised concerns that could cause alarm among members of the public and vets.”

Safety

It continued: “It is recognised that it is important that the safety of veterinary medicines, including environmental safety, is kept under review by companies and regulatory authorities to allow the medicine to remain on the market. However, there are other factors that must be noted when considering the recent paper.”

Among these, it said use as biocides and in greenhouses “are other possible explanations for the higher frequency of detection near sewage treatment plants”, while “actual evidence of environmental damage being caused by veterinary medicines in these rivers has not been demonstrated”.

The policy statement concluded: “Veterinary medicine manufacturers take the safety of the products they market very seriously. When new data highlights possible causes for concern, these are carefully evaluated by the regulatory authorities and any emerging risk is balanced against the substantial benefits that these products bring to animals, their owners and wider society.

“The Perkins et al paper demonstrates that fipronil and imidacloprid were present in English rivers between 2016 and 2018, but neither the source of this, nor whether it was environmentally damaging at the measured levels, is anything other than conjecture. Until further evidence becomes available, the current approach to environmental risk assessments for companion animal parasiticides is considered to remain the most appropriate.”

‘Be more mindful’

Responding to some points raised by NOAH, Mr Whitehead said: “Fipronil has had very limited agricultural use in the UK, with no recorded use after 2015 when less than 1kg was applied. Imidacloprid has no recorded outdoor agricultural use after 2016, when 186kg was applied.

“By comparison, Anthe et al report around four tonnes of imidacloprid is applied annually in flea products.”

He added the Anthe et al paper “did not assess all possible pathways of imidacloprid from pets to waterways” – for example, “the impact of dogs swimming in rivers” and “of people washing their hands after applying flea treatments, or after touching treated pets”.

Uses

On other explanations for contamination suggested by NOAH, he said: “Fipronil is licensed for use in only five ant and cockroach bait products, only one of which is licensed for use by non-pest control professionals. By comparison, there are 66 veterinary medicinal products containing fipronil.

“While imidacloprid is authorised for more diverse uses than fipronil, the high correlation between fipronil and imidacloprid concentrations across the different river sample sites in our study suggest they are coming from a similar source or pathway, such as topical flea products.

“Though only a few drops are applied to individual animals each month, they are toxic to aquatic invertebrates at extremely low (parts per trillion) levels. As a profession, we need to be more mindful of the environmental impact from large scale, indiscriminate pesticide use across millions of animals.”

- This story is in this week’s Vet Times (Volume 50, Issue 49).

- For the full Perkins et al report, visit https://bit.ly/3o1hyeB

- The full Anthe et al report is at https://bit.ly/2Vak1qx

*Original article online at https://www.vettimes.co.uk/news/flea-treatment-contamination-of-rivers-conjecture-noah/