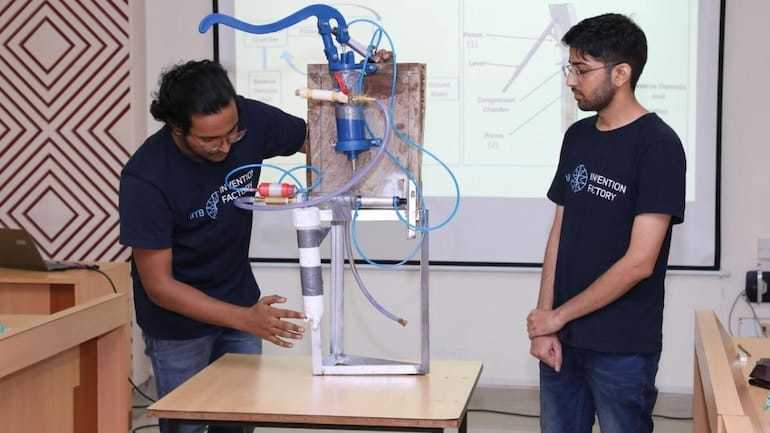

IIT Bombay students Arpit Upadhyay and Mohit Jajoriya have devised an RO hand pump that needs no electricity to generate clean drinking water, aiming to provide equitable access to rural India.

IIT-Bombay students Arpit Upadhyay and Mohit Jajoriya needed an out of the box idea for the upcoming Invention Factory programme in May this year.

The competition, they say, required students to come up with a product or tangible idea that can meet a significant need of society. When discussing what this could be, the two students, who had bonded during the lockdown period of COVID-19, found that they shared a deep and common interest in one particular issue — water security.

Mohit, who hails from Rajasthan, is pursuing his Master’s in Mechanical Engineering at the university. He says that back home, water quality is a worrying factor. “There is a high rate of desertification, and in most districts, the value of total dissolved solids (TDS) goes up to 2,000, when it should technically be no more than 500,” he tells The Better India.

Meanwhile, Arpit, who is pursuing his B Tech, says that in many parts of his home state Uttar Pradesh, the fluoride content of water is so high that people’s teeth turn yellow.

The two were united by their common wish for people in rural India to have access to clean drinking water. “People back home think that the dirty water is normal,” Arpit says, adding that when the Invention Factory competition was announced, they saw it as their chance to turn their ideas into solutions.

The result was their RO hand pump, with which they came up as runners up in the competition and won a cash prize of Rs 1 lakh. As per tests, the device can produce 1 lt of fresh water for an input of 7 lt of water.

‘Revolutionising an already existing principle’

During the six-week programme, Arpit and Mohit were participating among 10 groups of two students each. “In the first week, students are required to work on the proof of concept and present this before a jury,” Mohit explains. “The next five weeks are spent in making the model.”

“The jury,” he adds, “are people from different fields.” This is so that the winning idea is not assessed solely based on technology, but also in terms of ethical standards, impact, etc.

Week 1 saw Arpit and Mohit put their heads together to come up with an innovation that would be both sustainable as well as practical. “We didn’t want the solution to be far-fetched, in that it would increase the burden on villagers to get access to clean drinking water,” says Arpit.

This was the major idea behind their RO hand pump, which operates on mechanical power. Towards the end of June, they had sold the idea to their professors and the model was ready to present to the final panel.

Mohit says the pump is simply reverse osmosis (RO) without electricity. “We knew a traditional RO needs electricity for water to pass through the membrane. We decided to do the same, but replaced electricity with mechanical force,” he says.

He says the idea is based on a regular hand pump — a common sight in Indian villages. “Our research showed that there are lakhs of hand pumps in rural areas, around 50 lakh to be accurate. We thought if we could revolutionise an already existing principle, not only would the costs of installation be waived, but the villagers would also find it easier to adopt,” he adds.

The device works on a simple technology. Groundwater enters the unit and then passes through a pre-filtration part that comprises three filters — carbon, sediment, and ultra filtration. This ensures that dirt, odour, and micro-organisms are removed. “Until this step, it operates similar to the aquaguard at home,” says Mohit.

However, the next step is where the difference lies. “In traditional RO filters, there are compressors which require electricity. Water is pressurised in the compressor and then sent to the membrane. However, in ours, the water is first sent into a chamber, which is pressurised with a hand pump and mechanical pressure. This water then goes to the membrane, and is filtered,” he adds.

“There isn’t much that needs to be done if the model is being installed in villages,” says Mohit. “The hand pumps are already present and it is only the mechanism that needs to be modified. One RO filter can easily help eight to ten people get access to clean drinking water.”

A low-cost solution

The innovation was funded by the Maker Bhavan Foundation, and Arpit says it took Rs 47,000 to manufacture as there was a lot of trial and error involved.

“In theory, we had learnt that all it takes for water to pass through the membrane was pressure. But, in reality, things were very different,” Mohit says.

The duo found that initially, the pores in the membrane were tiny, so they would get clogged often. They also ran into a roadblock when they realised that any fluid, when pressurised, will start to leak.

They then began studying RO membrane and its technology, even resorting to using sealants and duct tape to stop the leakage. “Later, we started experimenting in our lab to get the hydraulics right,” says Arpit, recounting why this was all the more challenging, as the competition necessitates that students must work alone, and while resources are provided, there is no training given.

“No one teaches you how to go about using the machines in the lab. You learn these things yourself,” he adds. “We often spent days studying and manufacturing a certain part for the model, only to realise that it was a bad fit.”

Wasn’t that demotivating?

“Absolutely,” says Mohit, adding that their solution was to go to sleep and wake up with newfound enthusiasm the next day.

However, in retrospect, this has immensely helped them troubleshoot, they note.

He says the final product can be manufactured for Rs 5,000. “In the market, an RO filter costs Rs 15,000, out of which Rs 4,000 is for the compressor. Since our mechanism eliminates the use of the compressor, it is cheaper.”

Coming to the speed of the filtration, he says it is comparable to the RO filter at home. “The only difference is that the aquaguard at home is based on the principle of continuous water flow, while our innovation is based on pulsating flow,” he says.

The duo says that as per their tests, the pump reduced the TDS value of water from 800 to 300. They add that if the membrane dimensions are further improved, the flow rate will too.

“To make it clear, we are not claiming to give Bisleri quality of water with our device,” says Mohit. “We are simply aiming to make water that is drinkable available to rural India.”