Government scientists analyzed research by Solvay, which uses the chemical, and found link to liver damage, emails show

Update: On Nov. 10, the state of New Jersey filed a lawsuit against Solvay Specialty Polymers USA, alleging in part that the company has been using replacement PFAS at its manufacturing facility for more than two decades and polluting water supplies in the process.

A chemical introduced by the manufacturer Solvay Specialty Polymers USA to replace a now-regulated PFAS substance has been found in New Jersey drinking water, and the company’s own research suggests that it can cause liver damage, according to emails obtained by Consumer Reports.

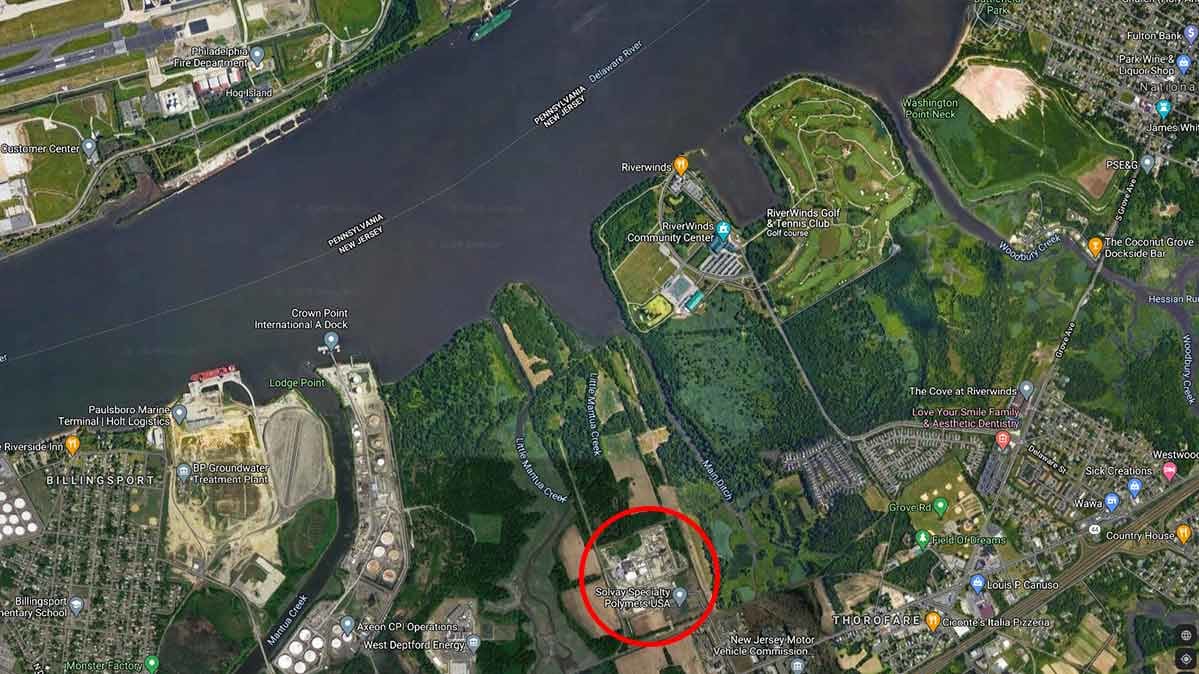

Solvay introduced the new compound as early as 2013, the emails suggest, to replace PFNA (perfluorononanoic acid), which the company used at its plant in the town of West Deptford to manufacture plastic components for consumer products. In 2018, New Jersey adopted strict limits in drinking water for PFNA, one of several thousand so-called forever chemicals, after preliminary research linked it to immune-system and liver problems. The state has attributed PFNA contamination (PDF) of soil and water around Solvay’s facility to the company, which denies responsibility.

Researchers from the Environmental Protection Agency and New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) revealed last month in the journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters that they’d detected a PFAS replacement in water that was “believed to originate from a regional, industrial user.”

The emails make clear that regulators believe Solvay is the source, according to internal EPA communication obtained by CR through the Freedom of Information Act. In addition, preliminary animal research indicates that the new compound is at least as toxic as the older chemical it replaced, the emails say.

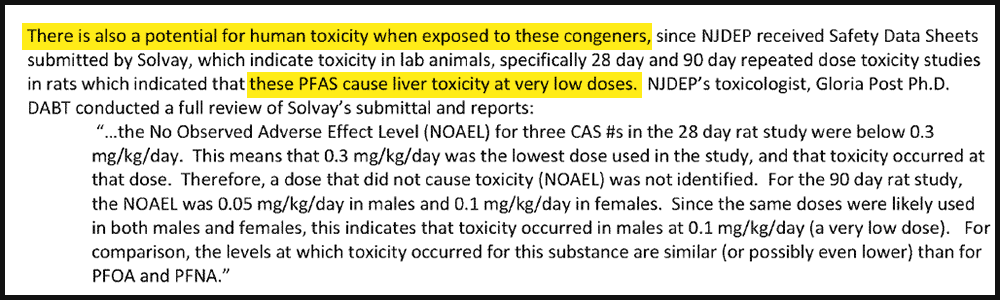

In an email from June 25, 2019, New Jersey DEP environmental specialist Erica Bergman told state and federal scientists that “Solvay’s replacement PFAS” had been detected in several private drinking wells. And an analysis of Solvay’s own research suggests that the compound poses “a potential for human toxicity,” possibly even at lower doses than PFNA or PFOA, another older, well-studied PFAS compound, according to Bergman’s email. That research, conducted in rats, “indicated that these PFAS cause liver toxicity at very low doses,” Bergman wrote.

The studies themselves weren’t included in the emails, and Solvay has previously declined to provide safety data on the replacement PFAS, claiming that the information is confidential.

In a statement, Solvay said research has not yet definitively shown that the chemical identified in the recent studies is one used by the company. And, the statement says, EPA and New Jersey DEP researchers acknowledge that their work was “non-targeted,” so the findings are “inherently imprecise.”

“These analyses, which were performed without any Solvay inquiry or consultation, are not substitutes for concrete analytical data using verified analytical standards,” the statement says.

Solvay has been using the PFAS replacement at its facility for years, despite not having implemented an official way for regulators or independent researchers to analyze whether the new compound is present in the environment, CR reported last month. And EPA and New Jersey DEP researchers wrote in the study published last month that “non-targeted” analyses have been “crucial” for identifying new PFAS compounds.

A spokesperson for the EPA had no immediate comment. The New Jersey DEP acknowledged CR’s questions pertaining to the documents describing Solvay’s research but deferred to a statement provided earlier that said the compounds are “expected to have toxicity and bioaccumulation properties” similar to well-studied PFAS.

Consumer advocates and PFAS researchers called for toxicity and safety information on Solvay’s replacement to be immediately released.

“The American people and the residents of New Jersey should be outraged,” says Dave Andrews, senior scientist at the advocacy organization Environmental Working Group.

“Recent studies found previously unknown PFAS compounds in soil and drinking water near a Solvay chemical manufacturing plant,” Andrews added. “These recent studies also noted a lack of public data on toxicity yet these emails reference Solvay’s own animal studies, which found their new chemicals to be as potent as PFOA or PFNA, two of the most toxic PFAS compounds. Why are these studies not public information?”

Michael Hansen, PhD, a senior scientist at CR, says that Solvay’s replacement PFAS were supposed to be “less toxic and less bioaccumulative” than PFNA, a point commonly asserted by industry groups and manufacturers who claim that new PFAS replacements are safer.

But in the case of Solvay, Hansen says, the preliminary data suggests that this is not the case.

“All the toxicity data that Solvay has on its PFAS replacement should be immediately released, and an accurate detection method must be developed for measuring levels of these compounds in water and soils,” he says.

‘Did Not Know to Look for This Compound’

The emails underscore the challenges regulators face in overseeing the use of new types of PFAS being used by companies, a reality that has prompted some advocates to call for PFAS to be managed as a “chemical class,” rather than one by one.

The government’s investigation initially began in 2016 as part of an effort to identify the source of PFNA contamination in New Jersey, emails show. But the state was also interested in learning what could be uncovered by using “non-targeted analysis,” a strategy the EPA says can identify unknown substances that may be present in water, soil, or air, “without having a preconceived idea of what chemicals may be in the samples.”

Through those tests, and an examination of available literature, the researchers identified Solvay’s replacement PFAS.

“We did not know to look for this compound,” wrote John Washington, an EPA scientist and PFAS researcher, “instead discovering it using nontargeted analyses.”

‘There May be Ongoing Human Exposure’

The situation presents a pressing concern for New Jersey residents: They may be currently exposed to the Solvay compound, described in literature as ClPFPECAs, or chloroperfluoropolyether carboxylates.

“It is perverse that another toxic affront is being forced on the same people who have already endured and fought off the original damage caused by Solvay with the release of highly toxic PFNA for so many years,” says Tracy Carluccio, deputy director of the environmental group Delaware Riverkeeper Network, which exposed the PFNA contamination in 2013.

“It is imperative for public health that chemical safety studies, especially those on PFAS compounds that are known to harm health, should be public,” says Andrews, at the EWG.

The emails show that the EPA is indeed worried that New Jersey residents may have been exposed to the new Solvay compound.

“Given that we’ve detected the CIPFPECAs in . . . the region, we are of course concerned that there may be ongoing human exposures,” EPA scientist Andrew Lindstrom wrote in an email Oct. 22, 2019.

Manage As a Class?

The EPA has yet to issue an enforceable limit for PFAS in drinking water, instead providing only voluntary guidelines for PFOA and PFOS. Some states have stepped in to fill the void and have implemented legal standards for a handful of PFAS, like New Jersey did in the case with PFNA.

But the situation in New Jersey with Solvay follows another high-profile contamination case involving a replacement that was supposed to be safer than PFOA and PFOS. Several years ago, researchers in North Carolina discovered GenX—a PFAS substitute introduced as a replacement for PFOA—in the environment. But preliminary research found that GenX is linked to similar health issues ascribed to PFOA.

Erik Olson, senior strategic director of health and food at the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental organization, says the regulators’ concerns about the toxicity of Solvay’s replacement further underscore a need to manage all PFAS as a class, a proposal opposed by a major industry group as an unnecessary measure.

“New ones keep turning up virtually every day,” he says.

The concerns of that reality are reflected in the emails between the EPA and the New Jersey DEP. In 2017, as the investigation in New Jersey was underway, the EPA’s Lindstrom wrote to Bergman at the DEP to discuss findings coming out of a separate study in North Carolina.

Lindstrom was startled: Researchers there had uncovered scores of novel PFAS compounds in drinking water supplies, he wrote in an email to Bergman.

“It is truly scary to see so many weird chemicals in municipal drinking water,” he said.

Consumer Reports has a long history of investigating America’s water. In 1974, we published a landmark three-part series (PDF) revealing that water purification systems in many communities had not kept pace with increasing levels of pollution and that many community water supplies might be contaminated. Our work helped lead to Congress enacting the Safe Drinking Water Act in December 1974.

More than 45 years later, America is still struggling with a dangerous divide between those who have access to safe and affordable drinking water and those who don’t. Communities of color often are affected disproportionately by this inequity. Consumer Reports remains committed to exposing the weaknesses in our country’s water system, including raising questions about Americans’ reliance on bottled water as an alternative—and the safety and sustainability implications of this dependence.

In addition to our ongoing investigations into bottled water, we are proud to be partnering with our readers and those of the Guardian US, another institution dedicated to journalism in the public interest, to test for dangerous contaminants in tap water samples from more than 100 communities around the country. The Guardian and CR will also be publishing related content from Ensia, a nonprofit newsroom focused on environmental issues and solutions.

America’s Water Crisis is the name we are jointly giving to this project and the series of articles we co-publish on the major challenges many in the U.S. face getting access to safe, clean, and affordable water. We will share the results of our upcoming test findings with you. In the meantime, you can join our social media conversation around water under the hashtag #waterincrisis.

Chief Content Officer, Consumer Reports