In a small and charming tourist-destination town in northern Sonoma County, a local ballot measure has pitted a tiny but dogged band of activists against an unusual enemy: dentists.

Healdsburg is the site of a battle over water fluoridation that has drawn local political groups and the California Dental Association into its orbit.

Measure T asks Healdsburg voters to decide whether to ban fluoride in Healdsburg water until suppliers of the chemical compound can prove it’s safe and free of impurities.

It’s largely the passion-project of one Dawna Gallagher-Stroeh, a Rohnert Park resident who quit her job four years ago to devote herself to advocating defluoridation full-time through her nonprofit organization, Clean Water Sonoma-Marin. She rejects the many research studies that say fluoridated water is safe and believes fluoride is linked to thyroid problems, diabetes, reduced IQ and cancer.

Healdsburg has been adding fluoride to the water since 1952, but most of the rest of Sonoma County is not fluoridated, and county health officials say children have high rates of preventable tooth decay.

Photo: Michael Macor, The Chronicle

Above: Fluoride opponents Barbara Jean Rudd (left) and Dawna Gallagher-Stroeh post a sign in Healdsburg. Below: Water utility foreman Allen Roseberry collects a sample at the city’s plant.

The fluoride activists are quite aware there is little love lost between them and the dentists.

“It’s like, ‘Here they come with their tin-foil hats again,’” said Measure T proponent Barbara Jean Rudd, describing the dentists’ view of the antifluoride activists.

Although Healdsburg is small, the state association of dentists has vigorously opposed the measure and poured $20,000 into the effort to defeat it.

In its 4.4 square miles, Healdsburg has 12 dentists licensed by the California Dental Association. The lawns of most of their offices are peppered with signs reading, “No on T, Save Our Smiles.”

Shawn Widick is a Healdsburg dentist leading the charge against Measure T, with financial backing from the Dental Association. He called the new measure “malarkey.”

“Myself, as a practicing dentist, I get to see the results” of fluoridation, Widick said. “I don’t have to prescribe fluoride pills. … I do fillings on children, but not nearly the amount I would do in the other communities I’ve worked in.

“Why throw the China thing out there? Because a lot of people are paranoid about it,” he continued. “To me, it’s scare tactics.”

Measure T marks the second time in two years Healdsburg voters have been asked to weigh in on fluoride.

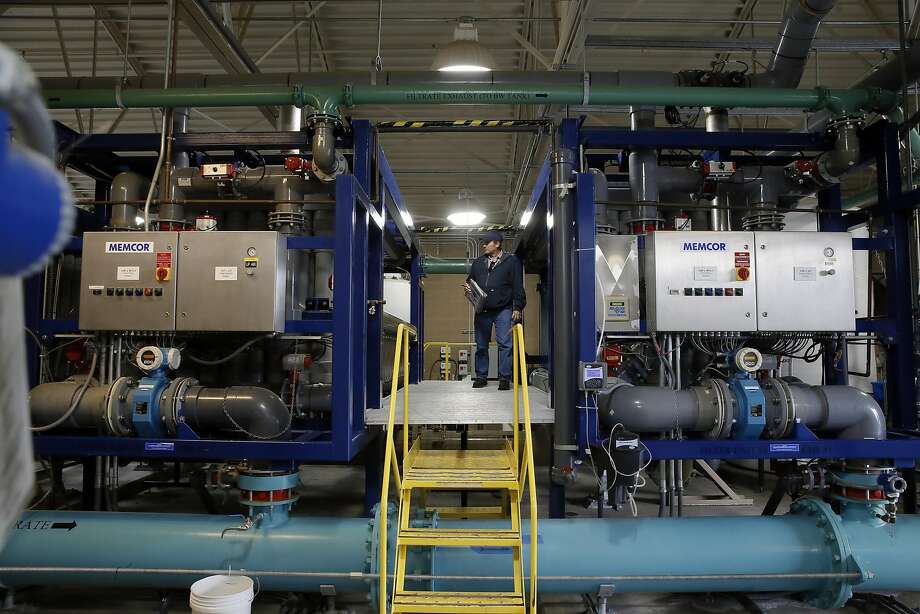

Photo: Michael Macor, The Chronicle

Allen Rose berry, a water utility foreman for Healdsburg, works at the town’s water treatment plant. Fluoride has been added to the drinking water since 1952, but an activist group wants it banned.

The 2014 measure simply asked voters whether the city should continue to fluoridate. Fluoridation won with 64.4 percent of the vote, although in such a small town, that meant only 1,183 more votes for fluoridation than against it.

This time around, the language is a little more complicated.

The text of Measure T reads, “Shall the City of Healdsburg institute a moratorium on water fluoridation in the city until such time as the manufacturer of the fluoridating chemical provides information regarding the identification of any contaminants in the fluoridating chemical batch, and a toxicological report and verification of safety for the fluoridating chemical?”

Gallagher-Stroeh and her allies say the request for proof of safety is amply reasonable.

But opponents argue Measure T’s requirements are so onerous, it would basically require a moratorium on fluoride.

“It’s so complicated the way that it’s worded that we’d probably just take fluoride out of the water,” Healdsburg Mayor Tom Chambers said when asked what might happen if the measure prevails.

Gallagher-Stroeh disagrees. “If they find a product that has proof of safety, they can continue to fluoridate,” she said.

Chambers and other members of the City Council thought the phrasing of the measure was confusing, so they tried to change it, he said.

The city changed the language so that the measure read simply “Shall the city of Healdsburg stop fluoridating its water supply?”

But Gallagher-Stroeh sued over the change, and a Sonoma County judge found in her favor.

In other pockets of the country, antifluoride activists have had some measure of success. Wichita, Kan., rejected fluoridation in 2012, and Portland, Ore., voted it down in 2013. Fluoridation also became something of a cause celebre among Florida Tea Party activists in 2011.

That year, the EPA and Department of Health and Human Services lowered the recommended intake level of fluoride, citing an increase in cases of fluorosis, the discoloration and in some cases pitting of tooth enamel.

In California, since 1995, water systems with more than 10,000 service connections have been required to fluoridate when funding is available to do so.

Some residents are wary of Healdsburg’s water because high lead levels were discovered at Healdsburg Elementary School in November. School officials took measures to prevent children from drinking from fountains or eating food cooked with the water but did not alert parents until February.

Some studies have found that the combination of chloramines and fluoride can have a corrosive effect on old pipes that makes the leaching of lead more likely.

Others in Healdsburg seem unconcerned with the state of the water.

Outside a local grocery store, Gallagher-Stroeh outlined the case for Measure T to one young woman, offering her a flyer and telling her to call if she had any further questions.

“Do you have my number? I’m going to give it to you,” she said, grabbing the flyer back and scrawling her phone number in the corner.

It was only a few minutes later, when she went to throw out the remains of her lunch, that she noticed the woman had thrown the flyer in the trash.