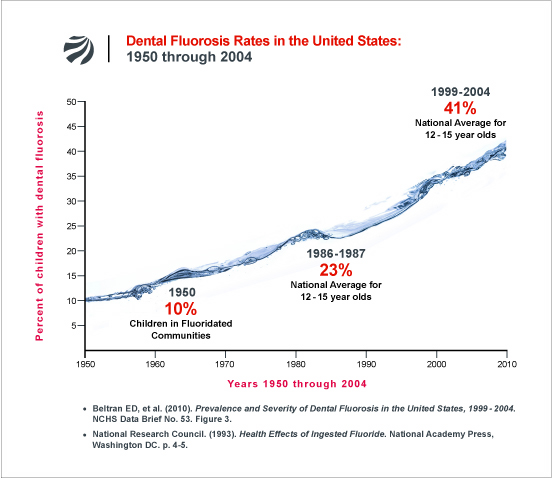

Before the widespread use of fluoride in dentistry, dental fluorosis was rarely found in western countries. Today, with virtually every toothpaste now containing fluoride, and most U.S. water supplies containing fluoride chemicals, dental fluorosis rates have reached unprecedented levels.

In the 1950s, it was estimated that only 10% of children in fluoridated areas had dental fluorosis, and only in its very mild and mild forms. (Hodge 1950; NRC 1993). Today, the most recent national data from the CDC shows that 65% of American adolescents now have dental fluorosis, with 3% of children having moderate/severe forms of the condition. The CDC’s national survey actually understates the fluorosis rate in fluoridated areas, since it includes children from both fluoridated and non-fluoridated areas. The rate of fluorosis in fluoridated areas is undoubtedly higher than 65%. Indeed, studies of fluoridated towns in the U.S. and Canada have found fluorosis rates to now reach as high as 70 to 80%. (Marshall 2004; Locker 1999; Luke 1997). Within fluoridated communities, studies have found that the rate of fluorosis varies by race, with the highest rates found among black children.

What Was Predicted vs. What Has Occurred:

The increase in dental fluorosis is particularly evident when using the “Community Fluorosis Index” (CFI) as the measure of fluorosis. As the analysis here shows, the current CFI for U.S. adolescents (including those from both fluoridated and non-fluoridated areas) is roughly 5 times higher than the CFI that was predicted for fluoridated areas when fluoridation was endorsed by U.S. health authorities in the 1950s. The following figure contrasts the CFI that was predicted with the CFI in the 1980s (as determined by the NIDR’s national oral health survey):

CDC’s Latest Data on Fluorosis Rates in the United States:

“In 1986–1987, 22.6% of adolescents aged 12–15 had dental fluorosis, whereas in 1999–2004, 40.7% of adolescents aged 12–15 had dental fluorosis. . . . The prevalence of very mild fluorosis increased from 17.2% to 28.5% and mild fluorosis increased from 4.1% to 8.6%. The prevalence of moderate and severe fluorosis increased from 1.3% to 3.6%.”

SOURCE: Beltrán-Aguilar ED, et al. (2010). Prevalence and Severity of Dental Fluorosis in the United States, 1999–2004. Centers for Disease Control. NCHS Data Brief No. 53.

Fluorosis Rates in Fluoridated Areas:

“The prevalence of fluorosis in permanent teeth in areas with fluoridated water has increased from about 10-15% in the 1940s to as high as 70% in recent studies…”

SOURCE: Marshall TA, et al. (2004). Associations between Intakes of Fluoride from Beverages during Infancy and Dental Fluorosis of Primary Teeth. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 23:108-16.

“The prevalence of fluorosis at a water fluoride level of 1.0 ppm was estimated to be 48% and for fluorosis of aesthetic concern it was predicted to be 12.5%.”

SOURCE: McDonagh, M. et al. (2000). A Systematic Review of Public Water Fluoridation. NHS Center for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York.

“Current studies support the view that dental fluorosis has increased in both fluoridated and non-fluoridated communities. North American studies suggest rates of 20 to 75% in the former and 12 to 45% in the latter.”

SOURCE: Locker, D. (1999). Benefits and Risks of Water Fluoridation. An Update of the 1996 Federal-Provincial Sub-committee Report. Prepared for Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care.

CONSENSUS: Fluorosis Rates Have Significantly Increased Over Past 70 Years:

“There is compelling evidence that the prevalence of dental fluorosis has increased in the United States and Canada in recent years.”

SOURCE: Warren JJ, Levy SM. (2003). Current and future role of fluoride in nutrition. Dental Clinics of North America47: 225-43.

“[T]he prevalence of dental fluorosis in the United States has increased during the last 30 years, both in communities with fluoridated water and in communities with nonfluoridated water.”

SOURCE: Fomon SJ, Ekstrand J, Ziegler EE. (2000). Fluoride intake and prevalence of dental fluorosis: trends in fluoride intake with special attention to infants.Journal of Public Health Dentistry60:131-9.

“Systemic F-exposure to children has increased. Mild dental fluorosis is now more common than one would predict on the basis of Dean’s findings in the late 1930s and early 1940s: in fluoridated and non-fluoridated communities. Several recent studies report prevalence rates in the 20 and 80 percent range in areas with fluoridated water.”

SOURCE: Luke J. (1997). The Effect of Fluoride on the Physiology of the Pineal Gland. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Surrey, Guildford.

“[A] few cases of more severe fluorosis can be found now in some communities. Because the prevalence of fluorosis is now higher than 50 years ago, we can conclude that fluoride availability… has increased in North American children.”

SOURCE: Rozier RG. (1999). The prevalence and severity of enamel fluorosis in North American children. Journal of Public Health Dentistry 59:239-46.

“There is a growing body of evidence which indicates that the prevalence and, in some cases, the severity of dental fluorosis is increasing in both fluoridated and non-fluoridated regions in the U.S… This trend is undesirable for several reasons: (1) It increases the risk of esthetically objectionable enamel defects; (2) in more severe cases, it increases the risk of harmful effects to dental function; (3) it places dental professionals at an increased risk of litigation; and (4) it jeopardizes the perception of the safety and, therefore, the public acceptance of the use of fluorides.”

SOURCE: Whitford GM. (1990). The physiological and toxicological characteristics of fluoride. Journal of Dental Research69(Special Issue):539-49.